In the mythological, quixotic and fantasy world of fly fishing the trout stream is ground zero. The point of entry, the wellspring, the source from which all knowledge and truth builds. A flow of water with enough gradients to create a compendium of pools, riffles, scours and structure with sufficient volume to harbor trout and grayling, yet not too big to become confrontational and intimidating. Up and down the Alberta Forestry Trunk Road and in the great Boreal forests of the north, Alberta anglers are blessed with a number of these tiny, perfect little fisheries. But not all rivers are in the category of comfortable little creeks that can be exploited with easy wading and short casts. Depending on your attitude, Alberta is either comforted or cursed with several main stem rivers that start big at their Rocky Mountain ice-field sources and only get bigger as they come charging out of the mountains and spread out once they hit the flat lands. The Oldman, Bow, Red Deer, North Saskatchewan, Athabasca and Big Smoky quickly come to mind. When it comes to fly fishing size does matter. Not only in the nature of the fishery but the dimensions of the fish that they hold. Big water usually means big fish.

But coming to terms with a wide expanse of moving water in which there may or may not dwell a feeding trout, can be problematic for a flyrodder more familiar with the intimate surroundings of a creek or small river. Where do you find a fish in all that water?

Reading the Water

When assessing a small stream fishery it immediately becomes obvious that 90% of the trout and grayling will be found in 10% of the water so that's where you focus your attention. On big water the math changes exponentially and at first glance most of the river appears to be deep and protected enough to hold fish. Unless they reveal themselves by actively feeding, trying to cover that amount of water is physically impossible, both because of the time it takes and the physical constraints of your equipment. So don't. Instead fish the stream within the river. This is the structure - some subtle, some obvious and close enough to the bank that you can comfortably cast to. Feeding fish will move out of their deep-water holding areas to the edges of a river. Here they will establish feeding lanes where shoreline structure creates seams and buckets that concentrate hatching insects and other food sources drifting in the current. So look for rock outcroppings, gravel kickers, drift-wood sweepers, undercut banks, foam lines back eddies, or anything else that causes a quickening of the current and a pocket of soft water behind it. Just as you would on an intimate foothills creek, ignore the big flow in the middle that you can't reach anyway and focus on what's before you. Some rivers like the Red Deer tailwater below the Dickson Dam, require the successful angler to sight fish for the big, but often scarce, brown trout that inhabit this stretch of river rather than randomly casting to likely holding water.

Here the angler often spends more time on the bank with his hook in the fly keeper than on the water, waiting for a buttery brown nose to show. Swinging a streamer like a Woolly Bugger or Zonker through the streambank can also be a productive way to economically search water when fish aren't showing.

Accessing the Water

Large rivers with significant volumes of water present the angler with additional problems not encountered on the archetypical trout stream. And that is access. On an average afternoon's hike up a compact Alberta trout or grayling creek an angler will easily fish through several dozen pools. If one doesn't yield a fish then there's another beckoning at the next bend, which will likely be only a few paces away. The scale of angling on a large river changes fundamentally. Instead of a smorgasbord of fishing opportunities - each with its own subtle uniqueness - the best a walk-and-wade angler can possibly hope to cover in a day is the number of pools that you can count on the fingers of one hand. So you have to pick your spots with care. Sometimes hiking to the next piece of fishy looking water is rendered impossible by impassible by cutbanks or bentonite oozes, while wading to the other bank is usually not an option.

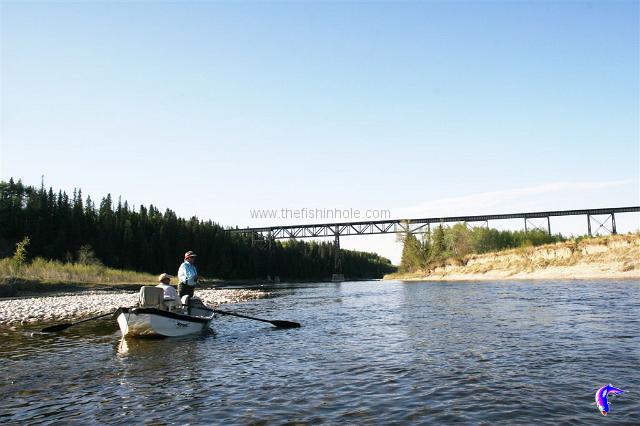

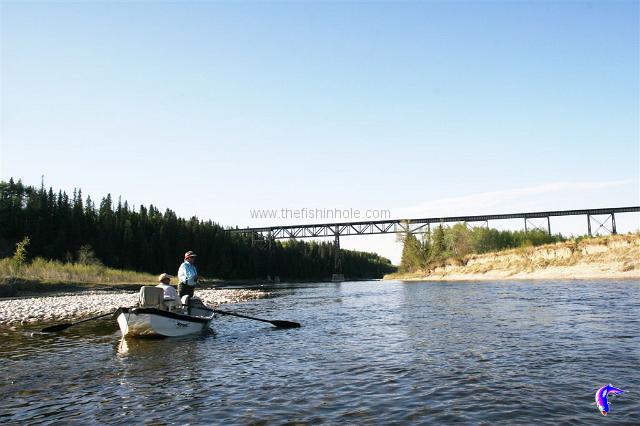

One way to even the big water odds is to drift the river. The classic way is with a MacKenzie boat where the oarsman controls the speed and direction of the boat with upstream stokes so the anglers can concentrate on covering the lies, most of which will be close to the shore. Rubber rafts are an adaptation of this while individual anglers can experience a lengthy piece of river in pontoon boats. Jet boats in larger and more remote rivers where conflicts with shore anglers and others are less likely are another option. Boats with standard outboard engines are not recommended, as is boating on big rivers by anglers who have little experience on moving and unfamiliar waters. But drifting comes with its own set of complications. Anglers can run many kilometers of river in one trip requiring either a shuttle service as is available on the Bow below Calgary, two vehicles, or a friend willing to drive your truck and trailer around to the takeout point. Drifting permits the angler to consume a massive amount of water in an outing, access the feeding lanes and prime water along both banks plus increase the angling experience by getting away from the concentrations of anglers at the bridges and launch ramps. A day on the river in a drift boat, raft or pontoon - complete with the traditional noon-time shore lunch - is a cosmic way to enjoy Alberta's great rivers. Fly fishing on the Big Boys can be extended well beyond the cold water zones which hold trout. Large migratory populations of free-rising goldeye inhabit most of the province's big rivers that can be accessed either by shore angling or by drifting, great fun on a dry fly when they're on.

Gear for Big Waters

Big water and big fish equates into bigger gear. The place for your delicate little 3 weight is in the rod rack at home when planning a big water visit. For dry flies and high stick nymphing, a 5 or 6 weight fly rod is more appropriate. But for pounding the bank with streamers or Woolly Buggers, as is often required on the Bow, an 8 weight is not out of the question. Reels loaded with both a floating line and something to get a streamer down to the pay zone is also recommended.

The big rivers can also carry heavy flows during the summer fishing months, either from mountain run-off, glacier-melt flows, and the infamous Alberta June monsoons or sometimes all of the above. Don't let this put you off. Fine angling can occur despite the high, off-color water. Some of the most prolific hatches of mayflies and stoneflies happen when the big rivers are swollen into the willows. It requires gearing up with enough split-shot to get a nymph rig bouncing off the bottom, or bright streamers weighted with cone or bead heads. Others like the Athabasca, Big Smoky and North Saskatchewan only come into their own when the glacier-melt slows down later on in the summer and fall. Thinking big means thinking differently, but when you make the necessary attitude adjustment, size only matters in the size of the fish the big waters produce.