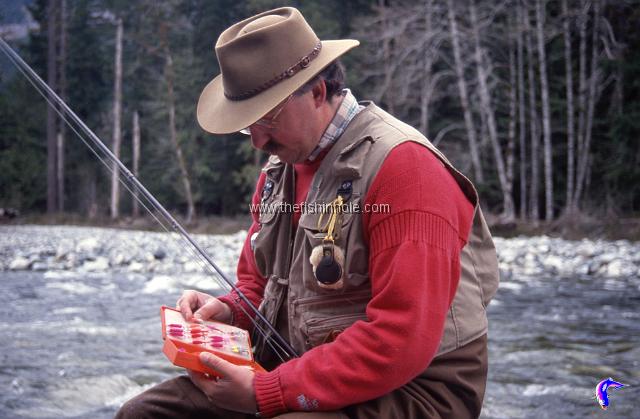

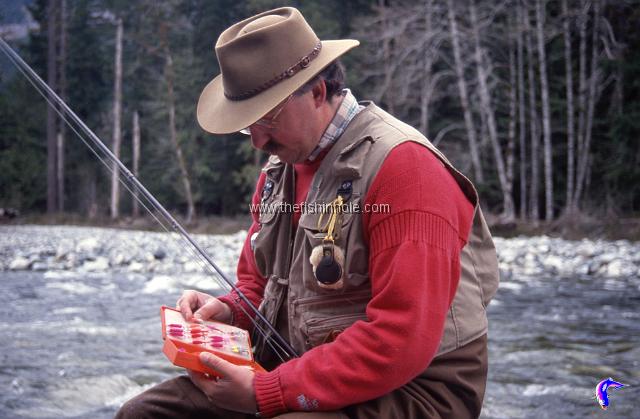

Not to put too fine of a point on it, but hooks are one of the most overlooked pieces of equipment for many anglers. Considering that they are your only real contact with a fish, it is surprising that few fishermen put much thought into their hook selection, especially given they make a significant difference in effectively presenting your bait, as well as, your ability to secure and land the fish.

Hooks originated long before any other fishing equipment. Speculation is that hooks made from wood, stone and shells were used in the Stone Age, and bone hooks dating back some 9000 years have been discovered in Palestine. Over time, hook material evolved, going from bone to copper to bronze to iron. The first modern hooks made from steel are noted in writings dated in the late 1400s. ade from steel are noted in writings dated in the late 1400s. By the 1600s, fishhooks were being manufactured for resale, and Izaak Walton, in his historic book from that century, The Compleat Angler, actually recommended purchasing hooks from London maker Charles Kirby. Hooks were hand made until the mid-1800s, when mechanized production took over. Today there is an amazing array of hooks manufactured, all designed for specific purposes related to angling technique, the lure or bait being used, and the mouth structure and size of the targeted fish.

Modern fishhooks are predominantly made from high carbon steel, though some use stainless steel or alloys. They are commonly characterized by the number of points they feature, with single, double or triple hooks being the norm; quadruple hooks have been manufactured but are not used for sport angling purposes.

Single hooks are the most common and are clear favourites for anglers fishing with bait. Virtually all flies utilize single hooks, as well as, an increasing number of lures, especially jigs, spinnerbaits and spoons. Proponents of single hooks argue that they make it easier to both hook and release fish.

Double hooks are relatively uncommon. They are used, however, on some Atlantic salmon flies, a few weedless lures and for some bait-fishing applications. Treble hooks are extremely popular for use on a wide range of manufactured lures, particularly on crankbaits, spoons and spinners. Every hook has the same general characteristics, including the eye, the shank, the bend, the point, and the gap. The eye is the part of the hook to which the line is attached. Though there are a number of eye shapes and angles available on the market, the vast majority of our angling applications are serviced with standard 'ball' eyes.

The shank is that section of hook between the eye and the bend. While hook patterns have a standard shank length, they are also available in longer and shorter than normal configurations. This variation from the norm is designated by the letter 'X'.

A long-shanked 2X hook, for example, indicates that the hook has a shank length equal to the standard shank of a hook of similar pattern two sizes larger. Some shanks feature curves or bends for increased hooking efficiency or for their appearance when dressed. Others have mini-barbs along their length for holding soft-bodied lures or baits in place.

The point is the sharpened, business end of a hook, designed for both its penetrating and holding ability. Most feature a barb, a projection that prevents the backward movement of the point once it has impaled a fish's mouth or a threaded bait. However, with barbless regulations common in many jurisdictions today, anglers are increasingly relegated to pinching their barbs down or purchasing factory barbless hooks where available. Hook sharpness from the factory has improved considerably in recent years, a result of advancements in manufacturing.

A chemical sharpening process that relies on a series of rinses in acids that shave a thin layer of metal from the point has resulted in factory hooks that require no extra sharpening before use. Most hook points lie parallel to the shank, though some are offset, theoretically to increase hooking efficiency.

The bend of the hook typically denotes the style by which the hook is named. Bend is paramount in determining the strength of a hook, and optimally it should resist bending almost to the breaking point. There are a number of different bend styles available on the market, each with its own attributes. Many are specialized for use with different natural baits. Lastly, the distance between the tip of the point and the shank is known as the gap.

All fish hooks are designated by size, though it should be noted that sizes are not identical between manufacturers. The size designation is largely a measure of the gap of the hook, and as such can also differ widely depending upon the hook style. Smaller hook sizes are denoted by whole numbers, the number getting larger as the hook gap gets smaller. Larger hook sizes are designated by fractions, with 0 as the denominator, the hooks getting larger as the numerator gets larger. The smallest hooks, depending upon the manufacturer, are sizes #28 through #32; the largest hooks range from 14/0 up to 19/0.

In Canada there are few applications for hooks smaller than size #24, which are used on some of the smallest dry fly patterns. At the other end of the scale, it's rare to find hooks larger than 8/0, which are used on some of the largest spoons and crankbaits.

The diameter, or gauge, of the wire used in fishhooks has a direct bearing on their intended application. Gauge impacts both a hook's strength and its ability to sink through the water column. The lightest gauges are used for light line fishing, with delicate baits or in floating applications. Heavier gauges are suitable when fishing for large fish or with quick-sinking baits.

Several factory finishes, providing both corrosion resistance and aesthetic value, are available, though corrosion resistance is not as important in freshwater situations as it is in marine environments. The common bronze-coloured, varnished tint found on many hooks is suitable for most applications and they do provide benefit if a hook breaks off in a fish's mouth. Studies have shown that in freshwater, standard varnished hooks will break down to the point of being brittle and corroded, though not totally decomposed, within two to three weeks. Stainless steel hooks, alternatively, take an undetermined time to decompose in fresh water, and in fact require several months even in highly corrosive salt water.

When making tackle decisions, hooks should not be overlooked or ignored. They are an important component of a balanced, effective tackle system. Anglers looking to increase their effectiveness on the water would be well served to think specifically about their hooks, matching them with fish size and species, other tackle utilized, and the presentation being used.