Like many Canadians, I found myself a little housebound after two years with little or no travel. In an effort to rectify the problem, my wife and I decided a little warm-weather break was in order, so in February we headed to the Bahamas for a couple weeks. More specifically, we went to Andros Island, long considered to be the "bonefishing capital of the world."

For those who’ve never fished for bones before, they seem an unlikely fish to attract all the attention they do. They’re not particularly large - although they can grow to exceed 10 pounds, anything over five is considered pretty big, and most are in the two- to four-pound class. They’re not an especially attractive fish - like a mountain whitefish they have a sub-terminal mouth, and they’re coloured somewhat similarly too, ranging from silver sides with slightly darker backs to olive - green backs that blend to the silver sides. And they’re certainly not known as being special on the dinner plate. Though I suppose, as with any fish, you could eat them, very few people do.

Bonefish aren’t especially pretty; their reputation is built on their fighting ability which is nearly unsurpassed.

No, what makes bonefish so popular with anglers, especially fly-fishermen, is that they always seem eager to eat, especially flies, and when hooked they punch well above their weight, fighting like few other inshore species do. Even a small bonefish will take a fly-angler into their backing with that first reel-screaming run.

It wasn’t by chance that we went to Andros. While we wanted to enjoy all the opportunities a winter vacation in the Caribbean offers, bonefishing was at the top of the list. My wife and I decided the smart thing to do was to hire a guide to help us get started, so we booked a half-day with a well-known local named Glaister, who has a great reputation in fly-fishing circles. On a somewhat cloudy morning, he loaded us into his flats boat and powered us a couple miles back into an inlet before shutting down the motor and poling us across the flats from a raised platform atop the motor. Height is a great advantage when you’re searching for these ghosts of the flats.

A typical flats boat with an elevated poling platform.

It wasn’t long before Glaister spotter a school of a dozen bonefish and poled us into position. I was stationed on a platform at the front of the boat while he directed my casting, calling out distances and direction. I was casting nearly blind as I couldn’t always see the fish he was targeting, but I managed to hook into one on my third cast. It took off like it had been shot out of a cannon, reminding me what all the bonefishing fuss is about. Before the morning was out I managed to hook two more, landing one of them, and was reintroduced to the challenges all bonefishers face, especially those, like me, without much experience.

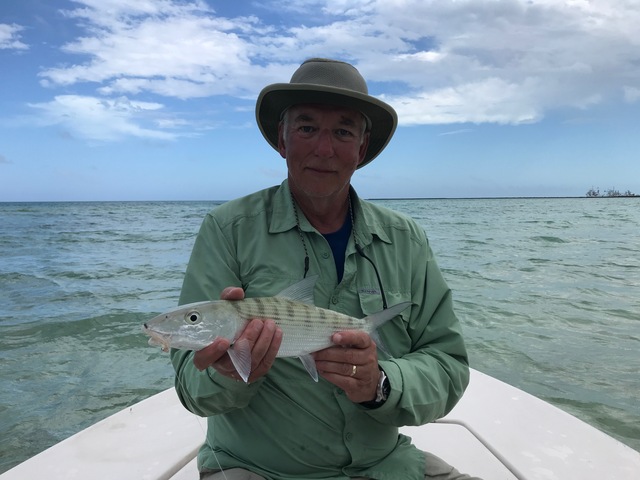

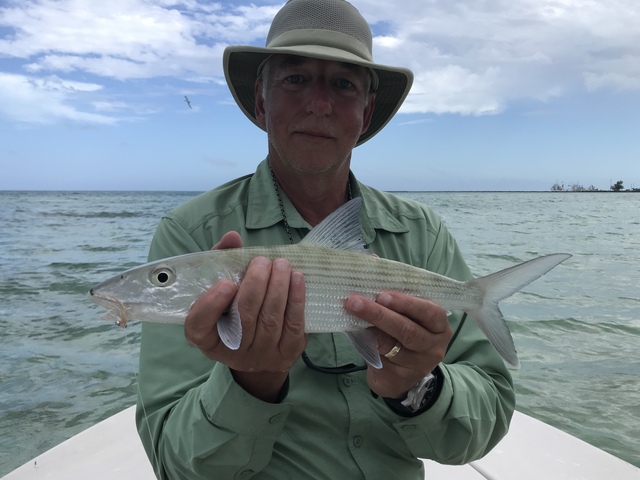

My first bonefish of the trip. Average bonefish are in the 2- to 4-pound class.

Seeing bonefish is the greatest barrier to catching them. The classic image of bones has them "tailing" as they move across the flats in search of crabs and other prey, head down on the bottom, their tail fin waving like a little flag above the surface. Over the five days we fished, I saw this behaviour twice. Most often they cruised completely submerged, and learning to see their pale bodies against the white sand bottom takes time and experience. It’s especially difficult to see them on cloudy days, I discovered.

Bonefish are especially difficult to see against a white sand bottom.

Then there’s the wind, and in the Bahamas it’s nearly always windy. Not necessarily gale-force, but enough wind that you have to account for it when casting. When fishing from a boat, experienced guides will try to position you so that you’re casting with the wind at your back, although it’s not always possible. Similarly, when walking and wading the flats, you can often, but not always, angle yourself so the wind isn’t in your face. The wild card in adjusting for the wind, however, is that bonefish are never stationary; they’re always on the move and sometimes you have to take your best shot in less than ideal conditions.

After getting an introductory lesson from Glaister, Jane and I spent parts of three days fishing on our own. The resort we were staying at would pack us a cooler and drive us to a nearby beach. We had two miles of shoreline to ourselves; over those three days we only encountered one other couple fishing one morning.

When fishing on our own, we had a couple miles of pristine shoreline to ourselves.

Fishing without a guide brought its own rewards, but one of them wasn’t catching lots of bonefish! Without the benefit of experienced eyes, or the height advantage of a poling platform, just finding bonefish was a challenge. Still, we managed to find a handful or two to cast to every day. We weren’t seeing schools of bonefish; most often we’d see two or three together. I learned a lot about bonefishing on those days, some of it the hard way. I knew to strip-set when a bone took my fly, resisting the urge to lift my rod tip as you would with a trout. But it took me a couple lost fish to learn that a strip-set is just an extension of the normal stripping motion you use to entice fish to take your fly. Twice I lost fish because I strip-set too aggressively and broke off or pulled the fly out of their mouth. Included in my mishaps was breaking off the biggest bone we’d see on our trip, a girthy fish that would have gone five pounds.

Fishing on our own also taught us to watch the tides carefully (bonefish are most active on a rising tide) and that stingrays and sharks, including at times aggressive bull sharks, are surprisingly common in these shallows. We also discovered that this is a game of patience and persistence, and that you can get a tropical version of snow blindness staring at the water all day as you search for fish.

I even managed to catch a little permit, the most desirous and difficult of the flats fish to hook.

On our last day we decided to hire another guide, this time for a full day’s angling. Jane still hadn’t landed a bonefish and we wanted to cross that off our bucket list before we left. Ricardo was the answer. He helped Jane with casting suggestions and was wonderfully patient as she learned to handle the wind and extend her distance. In fact, she took shots at 19 different individual or groups of bonefish before she hooked up! When she finally did, she handled the fish like a pro, and before the day was out we’d both caught several nice bones.

Jane and Ricardo with Jane’s first bonefish. She earned it!

Bonefishing is an addictive enterprise; you can’t do it once and move on, satisfied. We’ll be back, if not to the Bahamas than to somewhere else where silver ghosts cruise the flats. If nothing else, bonefish are one more good reason to get away from a Canadian winter for a week or two.