I cut my fly-fishing teeth on Alberta's infamous Bow River, a river that earned its reputation on the basis of big fish and big water. Through my first few years of fly-fishing, in fact, that's the only body of water I fished. And while the Bow was, and continues to be, blue-ribbon trout water, it doesn't come without its liabilities: the fishing can unpredictable; the dry fly action that was initially responsible for much of the Bow's press is inconsistent; the river has become more crowded over time, and; after a while you find yourself fishing the same banks, the same runs and the same pools time after time. There's nothing wrong with all this, of course, especially if your primary interest is to hook into big trout. But to fish the Bow repeatedly means sacrificing some of the simple beauty and the solitude that attracts many to fly-fishing in the first place.

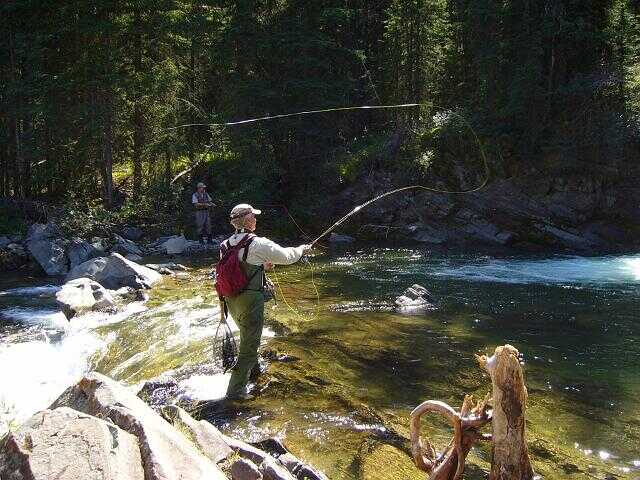

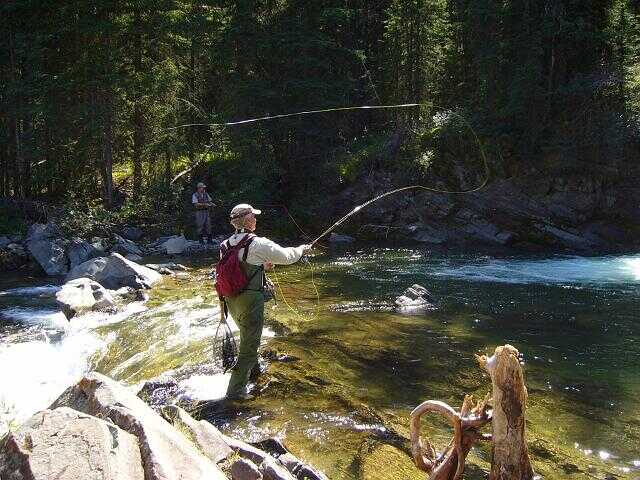

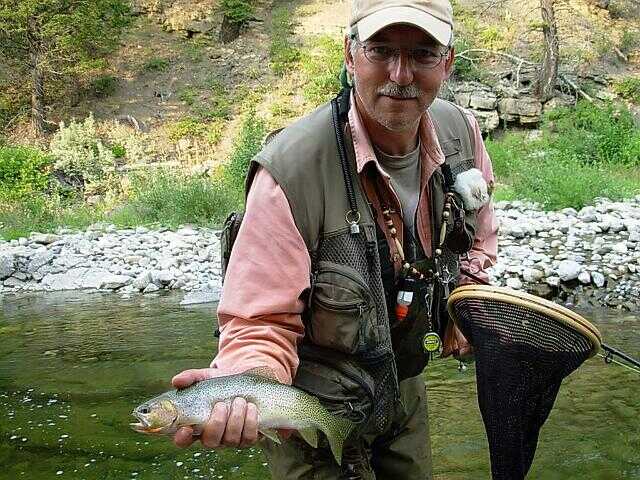

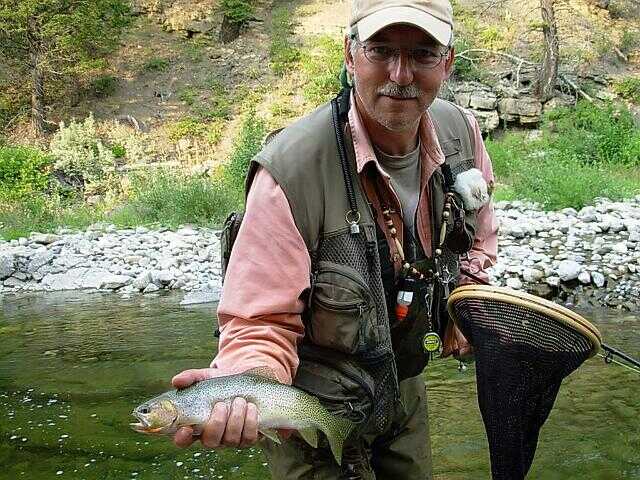

I still fish the Bow every year, but over time I've found myself spending more and more days on the smaller streams and creeks that lace their way through the mountains and foothills of Alberta's eastern slopes. I enjoy the relative privacy I find on smaller waters, the scenery is nothing less than spectacular, and the water is often plumb full of eager, hungry trout. What more could you want? Big fish, you say? Well, I'll admit that if you're only interested in 20-inch fish you're liable to come away from these small streams disappointed. Just remember that size is relative, and a scrappy 12-inch cutthroat on light tackle can put up a dogged and determined fight. Further, big things can come in small packages; every so often water you can spit across and doesn't seem deep enough to drown a chipmunk gives up a broad-shouldered cutthroat, rainbow or brown trout that pushes the tape to 16, 18 and even the magical 20-inch mark. And once you've battled to keep one of these lunkers out of the deadfall on a gossamer-thin tippet, you'll never again look at small streams in quite the same light.

Small streams are usually best fished with shorter fly rods; a 7- to 8-foot long rod built to handle a 3 to 5-weight line is probably about right. My personal rod of choice for these waters is a 7-foot 9-inch 4-weight that is relatively "slow", meaning that it is fairly flexible through the tip and middle sections. If you are fishing creeks with considerable stream bank cover that necessitates roll casting, you may want to select a stiffer, faster rod. Your personal casting motion can also have a significant impact on the right choice of rod for any water. If you tend toward a strong casting action you will probably find more satisfaction with a faster rod than someone who prefers a slower casting motion.

Floating lines are the best choice for virtually all small stream situations. I prefer a weight-forward line as it is easier to load in short casting situations and allows me to "punch" flies more effectively under windy situations, but there is an argument to be made for double-taper lines on small water. This is particularly true on the flat water conditions particular to many spring creeks where wary trout can be easily put down by the slap of a fly on the water, a scenario more likely to occur with a weight-forward line.

The standard leader for small streams is eight or nine feet long in either 4X or 5X, sizes well-suited for flies in the #8 - #18 range. After you break off a couple times on the shoreline vegetation (and let's face it, we all do that on occasion), you'll need to tie on extra tippet material. Again, 4X or 5X will handle most situations depending upon water clarity, the fly you're using and the size of the fish present, but I always have a spool of 6X along. I find that 6X is helpful where the fish are extremely skittish or when I am using very small flies (sizes #18 - #22).

Your choice of flies does not need to be as elaborate as some would have you believe. The cold water and steep gradients common to many small streams means that the water is less productive than further downstream on bigger waters. This translates into aggressive, hungry trout. When you don't have as many choices on the menu as you'd prefer, you tend to eat whatever is dished up, and eat it quickly before the opportunity is lost. If an angler were to carry a selection of elk-hair caddises, Royal Wulffs, Adams', Stimulators and Griffith's gnats in sizes from 8 - 22, I'm sure you'd be in good stead to fish 90% of Alberta's small streams 90% of the time. In fact, almost any "attractor" pattern will do the trick most days. The exception is on some of the spring creeks, where higher productivity and more constant water flows lead to highly educated and increasingly selective trout. These fish know what a meal on their home turf should look like.

As a result an angler has to be more careful about matching the hatch, particularly as it relates to the size of the fly. Nymphs definitely have a place on small streams, often turning more trout than dry flies will. The trade-off, of course, is that you lose the visual appeal of fishing dries. But there are occasions when trout simply refuse to come up, and when I find myself in that situation I'll tie on a bead head prince or gold-ribbed hare's ear nymph. I generally carry them in sizes 12, 14 and 16.

I'm often asked about leader length used when nymphing. As a rule of thumb, set your indicator above your fly at a length 1.5 times the average depth of the water you're fishing. When you cast into a run or riffle you should feel your nymph bumping bottom every so often. If you're not hanging up occasionally, crimp on a small split shot or two about 18" above your fly, adding only as much weight as you need to get your nymph to the bottom.

A common tactic employed by many experienced fly anglers is to tie a nymph on an 18- to 24-inch piece of tippet material directly to the eye or shank of a dry fly. Your dry fly acts as the strike indicator, while concurrently presenting a second opportunity to feeding trout. Your nymph should be at least one size smaller than the dry, and should be tied to a length of tippet one size smaller than the tippet to your dry fly. Anglers who fish this method will need to slow down their casting stroke to help prevent the two flies from tangling repeatedly. You can expect to hook fish not only on both the nymph and the dry, but every so often you'll enjoy a true double-header.

Even streamers have their place on small streams. Some of these waters have surprisingly deep pools and undercut banks. Trout like to hide in the safety and cool of these locations, making them difficult to tempt with dries or nymphs.

When I am faced with this type of water I'll often tie on a beaded or conehead woolly bugger or other leech pattern in size 8, 10 or 12. Unlike with dries or nymphs, which are generally fished upstream, streamers can be easily and effectively worked from above, below or beside a likely looking lie. For that reason, many angler fish upstream with dries and/or nymphs, then tie on a streamer and fish their back down to their starting point at the end of the day.