Beauty is a highly subjective notion, yet ironically, one that all of us deem ourselves qualified to state authoritatively on. Over time I’ve come to believe that the Arctic grayling personifies all that I consider beautiful in a fish, though I find great difficulty in articulating a defense of this assessment when challenged by those who view it as little more than a whitefish that showed up overdressed to daily roll call. The piscatorial list of traits that typically contribute to a fish ascending to the throne of elegance and desire are, by and large, absent in grayling when evaluated by even the most biased of anglers. They certainly don’t boast the symmetric, stylish and sleek lines of those fish that generally come to mind when a more classic definition of beauty is the measuring stick. Rainbow trout, Atlantic salmon and steelhead traditionally sit at the front of the class under these criteria. The grayling also can’t boast the near garish, colourful appearance of Arctic char, brook trout or even sockeye salmon when clad in the ornamental hues of their spawning period. Further, the grayling lacks the brooding, mysterious allure of a brown trout, the playful, “fish next-door” attractiveness of a smallmouth bass, or the brutish, rogue appeal of a muskie. No, at best the grayling can generously be described as quirkishly pretty; its mouth is too small, its eyes and scales too large, and its sail-like dorsal fin outlandishly ill-suited to its body size.

Despite its obvious physical shortcomings, I immediately think of grayling when talk of beautiful fish arises. Upon reflection, maybe it’s because I’m an ardent advocate of the Victorian English philosopher of biological and social evolution Herbert Spencer’s assertion that, “The saying that beauty is but skin deep is a skin-deep saying.” Grayling warm my heart, not because of their physical attributes, but rather in spite of them. It is the assemblage of all of the attributes that define a grayling that bring them so quickly to mind for me.

My first experience with artic grayling came some twenty-five years ago. A friend and I were paddling the Big Salmon River, a tributary to the burly Yukon River. The Big Salmon winds its way from its headwaters at Quiet Lake, adjacent to the highway between Tagish and Ross River, to its confluence with the Yukon River near Carmacks. The upper stretch of the Big Salmon was a carnival ride of rapids, riffles and hairpin curves, punctuated in the name of adventure by hidden log jams and sweepers that emerged stealthily from the recesses of the heavily treed shores. Within two hours of our departure we’d beached on the pebbled, inside turn of a right-angled curve, in part to find respite from the exhausting stretch of river we were only part way through, but more practically to repair the golf ball-sized hole we’d punched in the fiberglass hull trying to twist our way through a chicane of sunken deadfall. As my partner set about the repairs with a mixture of superglue and duct tape, I pulled out my ultralight gear, tied on a Mepps spinner, and tossed the lure into the transition between a riffle and the corner pool. Immediately I had a fish on, and in no time was holding aloft a wriggling 14-inch grayling. Three more casts produced three more fish, and by the time our canoe was again pronounced fit for duty, we had a fresh supper on ice in the cooler. For the remainder of that week, cooperative grayling provided both recreation and sustenance for us, and it’s the fishing fun we enjoyed that comes to mind most readily whenever I think back to that trip.

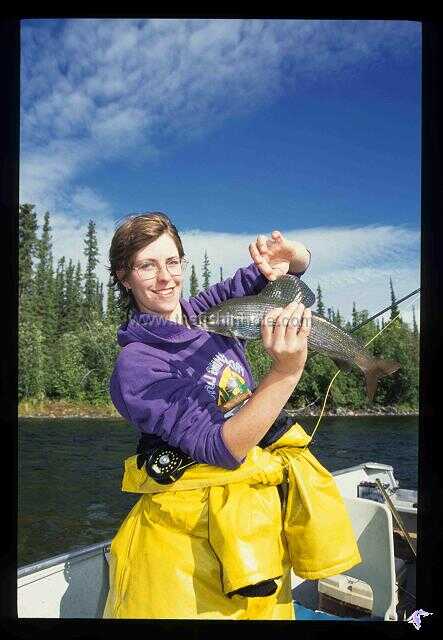

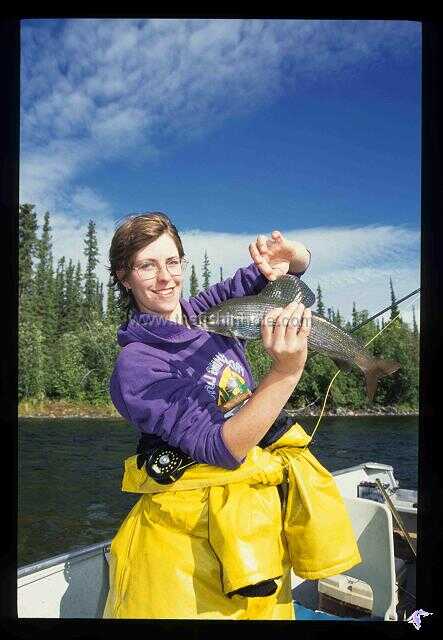

Now before I go any further, it would be unfair of me to dismiss outright the physical appearance of grayling as not contributing to their appeal. For while they may not stand up to the most critical aesthetic judgments, they are not without their own array of inherently attractive features. Foremost among these is their colouration. Often described as being gray with purplish spots, this pedestrian description does not do justice to the hues of lavender, magenta and lilac that reflect in the right light from their spotted pewter flanks when first pulled from the water. Unfortunately, in keeping with the precedent established by the Aurora borealis that shimmers in multi-coloured splendor across the night skies above the waters that grayling call home, the best grayling colour shows are short-lived. In just a few short seconds after emerging from the water, their complexion loses most of its vibrancy. Blink too long and you’ll miss it

Even their sail-like dorsal fin has become an endearing feature to me. Much like your favourite uncle with the big nose, you soon fail to see the oversized appendage as a feature unto itself. Eventually it just becomes one component in a greater whole, and if it were ever to be altered or removed the remaining composite would be lesser for it.

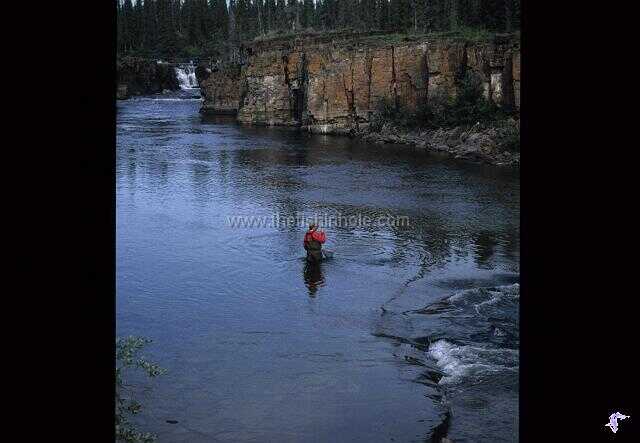

One of the grayling memories etched most indelibly in my mind occurred very early one morning on a reach of the Stark River, at the eastern extreme of Great Slave Lake. We were staying at Frontier Lodge, predominantly fishing for the monster lake trout that ply the lake’s frigid depths. But as an avid fly angler, I didn’t want to pass up the chance to tease a few of the grayling that inhabit the river right below the main lodge, and so slipped down to the river just as dawn broke one morning; a cool August morning and a river full of fish to myself was just too much to resist. I’d hooked a pretty decent sized fish, in the 20-inch range, and it was giving me a worthy tussle, taking full advantage of the bubbling rapids above a natural ledge. As I was focused on the fish, the wolf was some twenty-five feet into the water before I noticed it. Snow white in colour, it had obviously been lured from cover by the struggling fish, and had slipped from the cool spruce forest on the far bank to investigate what must have appeared, at first glance, to be an easy meal. The wolf either didn’t notice me attached to the other end of the determined grayling, or else it viewed me as a threat worth risking in return for a breakfast of fresh fish. Upon my realization of the wolf’s presence and intentions, I stopped reeling and let the grayling continue to dance at the end of my line. The wolf, no more than forty yards from where I stood thigh-deep near the opposite bank, was clearly having difficulty with the river. Above the ledge, the turbulent water made walking out to the fish all but impossible for the determined predator. With every step he would fight to maintain his balance against the rough water. Retreating to shore, he ventured out again, this time in the smooth water below the ledge. But here the water’s depth forced the wolf to swim, and the current would quickly pushed him downriver, again foiling his attempts to close in on his prey. After repeated attempts both above and below the ledge over the course of five minutes, the drenched wolf finally turned away and trotted upstream, offering what appeared to be an indignant shrug of its broad shoulders before disappearing back into the quiet of the forest. It was an experience I would have loved to have shared with someone, but was somehow made more special for having enjoyed it alone.

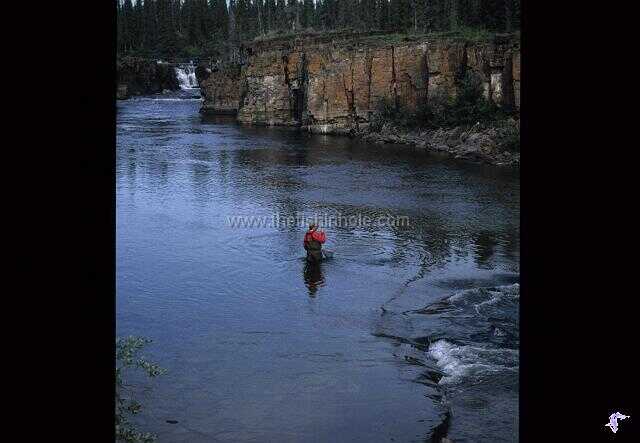

Arctic grayling have a reputation for being easy to catch. Though this rap is somewhat undeserved, admittedly there are times when they can be easily fooled, making them an ideal fish for novice anglers. Eager, rather than easy, might be more fair to them. It was once such occasion that brings to mind what is probably my favourite recollection of grayling fishing. At the time, my wife Jane had never previously hooked and landed a fish on a fly rod. It was our last day of fishing at Plummer’s Lodge on Great Bear Lake, and instead of another eight hours on the big water in search of lakers, we took up the alternate offer to spend the day on the Sulky River, a quiet grayling stream that spills into the massive lake. We fished less than a mile of the river as it gurgled between two small lakes and literally caught as many grayling as we cared to toss a #12 elk hair caddis imitation to. The river tumbled over a series of ledges, with the pools between the drops as clear as the skies that favoured us that day. Jane landed a couple handfuls of chunky grayling, the best nosing 20 inches and three pounds. It would be difficult to imagine a more pretty setting for enjoying one’s first fly-fishing success. All the fish hit our flies with a fervor that suggested they’d seen few artificials in their day, and fought with a tenacity befitting a creature that lives in such a pristine wilderness. I fished one canyon section in the river that still stands as the prettiest piece of water I’ve yet waded, and to have done it with Jane beside me was sweet icing on an already fulfilling cake.

When all is said and done, I suppose the immense attraction I have for grayling is as much a reflection of the wild places these fish call home as it is the fish themselves. They are sensitive to disturbance and over fishing, and where grayling thrive today will tend to be among the most remote and captivating wilderness waters you could hope to find. I find few things in life as enjoyable as casting to these northern icons under a powder blue sky, with nothing but miles and miles of nothing but miles and miles all around me, and I will continue to seek new opportunities to fish grayling across the four western Provinces, the Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut. The lure of the remote waters they call home is an intoxicant with no antidote for those who’ve fallen under their beguiling spell, and the venerable grayling encapsulates their charms in a simple, dependable and resplendent package. And what could be more beautiful than that.