In fishing, as in life, the little things make all the difference. For fly-anglers, the gap between success and frustrating disillusionment can be amazingly narrow; often it’s a simple mistake, repeated continually, that separates an angler from consistently catching trout. Following are a few of the more common mistakes I see.

Too Much False Casting

Watch an experienced angler do their thing and seldom will you see them make more than one or two false casts. Inexperienced anglers, meanwhile, far too often make six or seven. More often than not, the result is a pile of tangled fly line or a fly that lands nowhere near the intended target. With each successive false cast the probability of something going wrong increases, as it becomes increasingly difficult to control your line.

A common reason for excessive false casts is an unwarranted belief that you have to cast farther. But the laws of diminishing returns come in to play, and you’ll find that those extra false casts usually only get you a few extra feet, if any, and that’s provided your cast doesn’t collapse along the way. Accuracy is far more important than distance, and one or two false casts should do the trick. If you’re not getting your fly to the fish, move closer.

Limit your false casts to the fewest possible.

Not Letting Your Fly Work For You

Related to the tip above, a common mistake novice anglers make is ripping their fly off the water when it doesn’t land where they intended it to. Often, this has the unfortunate consequence of spooking the very fish they’re targeting. And others.

Trout use a wide range of microhabitats in a stream. Just because your fly didn’t land in front of the fish you were targeting doesn’t mean it won’t float over other trout on its way downstream. Let it float back to you; you might be surprised at the results and you’ll also reduce the amount of trout-scaring disturbance you make.

Avoid ripping your fly back when it doesn’t land where you wanted it to.

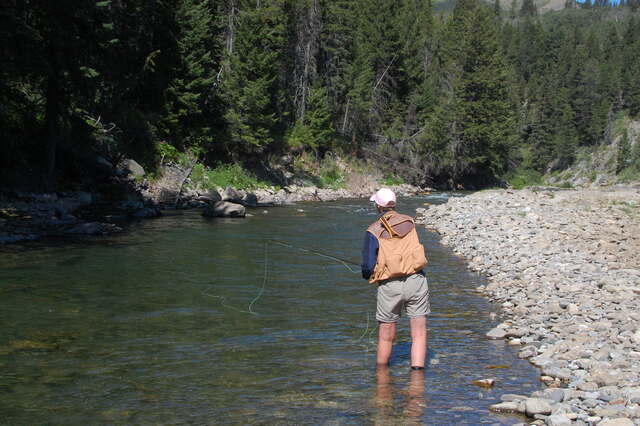

Getting Anchored in One Location

Rookie anglers will often stand in the river, not moving more than 10 feet, and cast and cast and cast, all without a single take. A lesson I learned from one of my fishing mentors, Barry Mitchell, was to fish good water thoroughly but quickly, and then move on. On quality trout streams there’s more good water around the next bend. Moving and covering water is one of the most effective ways to find fish, catch fish, and learn how to read a river.

When you’re not catching fish, it doesn’t necessarily mean you’re doing something wrong. It could mean there are no fish there to be caught. We’re creatures of habit and I, like many anglers, return to the same spots time after time. But I’ve learned that when my honey-hole isn’t producing, there are plenty of fish to be caught elsewhere, and discovery of the next great spot is one of the joys of fishing.

There’s always more good water ahead; move when you’re not catching fish.

Not Learning to Read Water

Learning to read a river comes only with experience. Each run, seam, riffle and pool can be different from the one before. You won’t become proficient at reading rivers overnight, but every rise and every take helps you understand where trout live, if you’re paying attention. Once you know where to look, catching trout becomes measurably easier.

Many novice anglers are overwhelmed when they first step into a stream; it all looks the same to them. Start making random casts and chances are you won’t catch fish. Begin by identifying some of the essential sections of a river, including riffles, runs, overhanging banks and pools.

These microhabitats all have features that trout use. Fish these areas thoroughly, making mental notes of where fish appear. Eventually, it will all become second nature to you, and you’ll be able to step into any trout stream and find fish.

Experience and attention to detail will help you understand where in a stream trout are likely to be found.

Trout and Currents

Despite what you may have heard, trout do not always face upstream; rather, they face into the current. This is a minor, but significant, distinction that should impact the way you approach and trout-holding water. When you encounter an eddy along a bank, as an example, the fish at its outside edge may actually be facing downstream, even though they’re nose-first into the current.

All instream obstructions will cause the current to veer. Watch for these current changes and remember that fish are most likely to be facing into the current, and plan your presentation accordingly.

Midstream obstructions impact current flow, and the direction trout are facing.

Not Matching the Hatch

You’ve heard it a thousand times, undoubtedly, but that’s because it’s so important. Trout can be frustratingly selective feeders, and understanding what they’re feeding on will often spell the difference between success and exasperation.

When you first get to a stream, it pays to sit for 10 minutes, watching the water and identifying where and how trout are rising. At times there may be an obvious hatch happening that will provide your first clue, but that’s the exception. More often, you’re going to have to pay careful attention to determine if they’re eating caddisflies, stoneflies, mayflies, hoppers or any of the other wide array of prey trout feed on. More importantly, try to identify whether they’re taking food off the surface or just below it. The air can be alive with mayflies, but if trout are feeding on nymphs just below the surface, your chances of fooling them with a dry fly are remote.

Success increases when you offer trout a fly replicating what they’re actively feeding on.

Manage Your Line

Slack line is usually not your friend. There are times when slack is necessary to get the right drift, but that’s the exception. Generally speaking, slack line only contributes to spooked fish or missed takes.

When a trout takes, you need to be in contact with your fly so you can set the hook at the right time. To do that, you must strip in excess line as your fly drifts toward you; failure to do so often results in the current grabbing that extra line and tugging it, along with your fly, in unnatural directions. One of the best ways to reduce unwanted slack is to move closer to your target. Avoid long casts whenever you can; short casts and improved line management increase your hookups significantly. Try to set the hook when you have too much line on the water invariably results in a missed fish.

Keep the slack out of your line as it drifts toward you.

Hold the line in your free hand throughout the drift. This helps keep tension in the line and allows you to better control your fly. Remember, too, that as exciting as it is when a trout eats your fly, make sure they get it fully in their mouth before setting the hook.